Grey Whales – The Tale of Their Extensive Journey

As the sheer ferocity of the waves and gustily gales of winter taper off; the residents of Tofino and Ucluelet shift their attention away from the storm-watching season. The annual Pacific Rim Whale Festival has recently drawn to a close, attracting the attention and excitement from whale and nature enthusiasts alike – with Grey Whales becoming the talk of the town.

The Grey Whales have begun embarking on their long migration meaning that Spring has finally arrived!

Every March, with news of their return, we’re excited to offer you the opportunity to venture out to the open ocean; to observe and appreciate these majestic mammals in their natural habitat.

Record Keepers for the Longest Migration Distance Covered

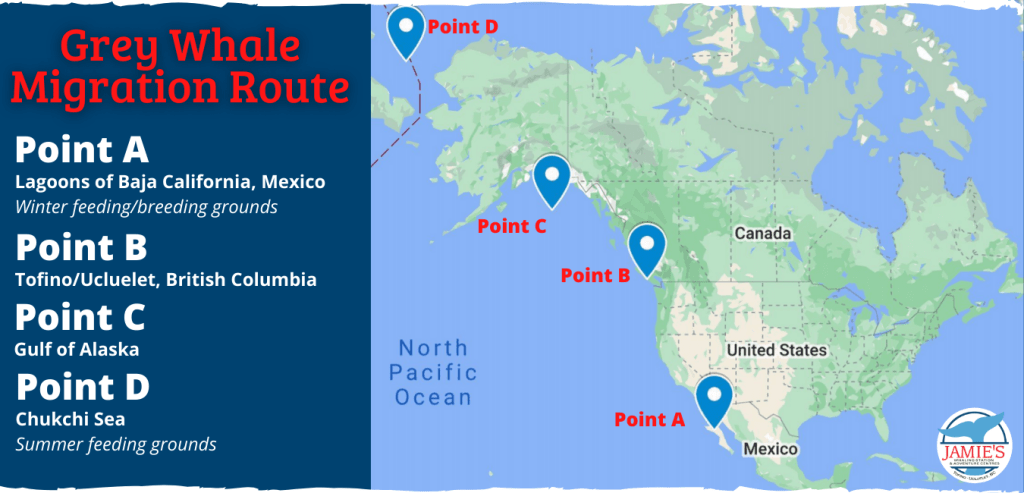

Along the coastal waters of Clayoquot and Barkley Sound, faint exhalations of mist are seen spouting upwards from the ocean surface. These ‘spouts’, are bushy and almost heart-shaped, marking the Grey Whales’ extensive journey from the south. They commence their migration from the breeding grounds located in Baja California to the colder waters around the Being Sea; beyond the Arctic circle with some whales going as far as the Chukchi Sea. The overall journey (round trip) accumulates roughly to 10,000 km – 20,000 km. This long expedition is currently one of the record holders for the furthest migration ever recorded by a mammal.

But why do these whales make this exhaustive/tiring journey? Why not remain situated in the warm southern tropic waters? What could possibly be the appeal to venture into the frigid waters of the Northern Pacific?

The answer is found within the most universal necessity of all living things: to find food.

While spending their time frolicking in the warm breeding grounds; Grey Whales will do without food for extended periods, resulting in them ‘fasting’ for several months. A Grey Whale – upon returning from the south, will have suffered a significant decrease in body weight…. up to 25%.

To put it lightly, they are famished!

Distinguishing Grey Whales Features

Ranked as the 8th largest cetacean (a marine mammal of the order Cetacea; a whale, dolphin, or porpoise); a Grey Whale ranges from 11 meters – 13 meters in size (comparable to the size of a school bus) and can reach a full bodily mass of 30,000kg. It does not have a noticeable dorsal fin – rather there are several noticeable bumps or ‘knuckles’ found along the ridge of the upper body of the whale, closer towards the fluke (tail).

The Grey Whales’ name is derived from the coloration of its skin, but do not let the name fool you. Grey whales are often covered with various yellow, orange, and white markings, produced from numerous barnacles and whale lice. These markings/scarring act as a fingerprint, creating a unique pattern that allows researchers and whale enthusiasts to identify them as individuals. By comparing photographs and cross-referencing with a photo ID catalogue (like the one compiled by the Pacific Wildlife Foundation found here); we can determine the age, sex, and sometimes the family tree of the whale.

A few of these curious encounters have allowed researchers the opportunity to recognize the same group of Grey Whales as recurring visitors to Clayoquot and Barkley Sound. These particular whales are deemed ‘Summer Residents’ – as they forego the migration towards the Arctic and remain around the area for the remainder of the season, drawn in by abundant food in the surrounding shallow bays.

What’s on the menu?

Grey Whales have a pretty unique feeding strategy when compared to other baleen whales. For the most part, they are found feeding at the sea bed.

Grey Whale Baleen. Photo by Jerry Kirkhart via Flickr

Wait a minute. Back up. What is baleen?

Baleen is a filter-feeding system, where several plates lining the inside of a whale’s mouth, with multiple long fibres that act as a strainer. The baleen allows water and sand to be filtered out, trapping the whale’s prey.

A Grey Whale will have up roughly 130 – 180 baleen plates on each side of its mouth. The plates are made of a special material called keratin, which is the same material your hair and fingernails are made from. Grey whales are benthic feeders – which means upon taking a dive, they will proceed to roll over to one side, and suck up mud/sediment with their mouth and scrape it along the bottom of the ocean floor.

By pushing all the sediment and water out through their baleen with their enormous powerful tongue, the tiny organisms hidden within are then trapped to be swallowed up as food. The diet of Grey Whales may consist of mysids, ghost shrimp, crab larvae, and amphipods (tiny crustaceans). These tiny organisms are often no bigger than a few grains of rice squashed together. During the early spring months, they will also feast on herring roe in areas around Clayoquot and Barkley Sound where there the herring are spawning. A Grey Whale must work extensively to get its fill – ideally about a ton of food per day.

Grey Whale feeding on herring spawn in Mayne Bay near Ucluelet.

If all the food is up towards the North – why head South?

Good question: the answer is to breed and reproduce.

The waters near the Arctic are indeed colder; essentially meaning there is a higher presence of oxygen, which supplies more nutrients to the ecosystem. More nutrients = more food for the whale.

Grey whales can survive the cold frigid waters of the Northern Pacific thanks to the insulative thick/fatty layer called blubber stored underneath the skin.

Born at a length of 4.5 meters and weighing approximately 1000 kilograms; calves are dependent on their mothers, as they are nursed on their mother’s milk for the first 6 months or so. The fat content of the mother’s milk is 53%, which allows them to grow at a rapid pace. After a few months of the calves being nursed and acquiring some more mass – the younger whales are then able to safely make the journey north with their mothers.

It’s important for Grey Whale calves to grow and put on mass efficiently as one of the major challenges they will face on their long journey North to the feeding grounds is predation attempts by families of Bigg’s (mammal-eating) Killer Whales. Adult Grey Whales are a large and dangerous proposition for a Killer Whale hunt, but young calves are much easier prey.

Grey Whales don’t spend their time in family groups like some whales. The only instances where a whale is seen in the company of others is either when they are gathering to breed, congregating in an abundant feeding ground, or when a mother and calf are travelling together towards the North. After a weaning period of 7-9 months, the offspring is then separated from its mother and fends for itself; even making the journey back to the South on its own.

How the young whale recalls its way back on its own – baffles researchers to this day.

Will I see Grey Whales on a tour after the migration period is over?

Jamie’s operates from two locations with an extremely diverse eco-system: Clayoquot Sound (body of water surrounding the Tofino Area) and Barkley Sound (body of water surrounding the Ucluelet Area) – each known for repetitive visits from Grey Whales known as ‘Summer Residents’.

Throughout the year, there are more than 100 whales that make up the Summer Residents population, who don’t make the journey to the Arctic and instead remain along the coast between Washington and Northern BC. They remain scattered across the shallow bays, tracking down their food, tucked hidden away underneath the ocean floor.

So even after the migration season is long over; the chances of seeing Grey Whales are high. Throughout the year, we’re lucky enough to see whales on approximately 95% of our tours. If you don’t see a whale during your tour, we’ll happily take you out again, free of charge.

There is a lot more to learn about these Gentle Giants, and our crew is eager, passionate, knowledgeable, and willing to share these facts with you.

We –The Jamie’s Crew – hope to welcome you aboard soon!

Written by Jean-Yves Daniel. Grey Whale photos by Ashley Hoyland – Naturalists for Jamie’s Whaling Station.